Experts weigh in on the agriculture capital continuum

What does a healthy agriculture capital continuum look like? We spoke to ag-investors about the types of capital that agribusinesses need.

- Blog

- Sustainable agriculture

- Cross region

If you’ve ever tried, you know that producing food requires so many things to go right. Now, producing food, processing and selling it, and creating a profitable business model around that is even harder. The complexity of growing food is an apt metaphor for the complexity of growing and capitalizing an innovative agribusiness in emerging markets during a climate crisis.

A ripe tomato or cocoa pod needs the right seeds, the right soil, proper weeding, and just enough sunlight. The list goes on, and it’s all interdependent. Without access to several interdependent financial instruments, available at just the right time and in the right quantity, the big, ripe, resilient ideas of agribusinesses that could transform our food systems risk dying on the vine.

So what does a healthy capital continuum look like for an early-stage agribusiness operating in an emerging market? What do the set of instruments and investment paradigms look like that are fit-for-purpose, with alignment around risk, returns, and tenor? To unpack these questions, we spoke to several other ag-investors including FINCA Ventures, elea, and Mercy Corps Ventures.

What emerged was a clear set of capital instruments requirements and an equally clear set of gaps: working capital, early-stage equity, and scale equity. Investors also noted the elephant in the room: a halting lack of exits. Other sectors may have similar capital needs, but the size of the financing gap and the need to re-evaluate return expectations pose a unique challenge to agriculture.

Components of a healthy capital continuum

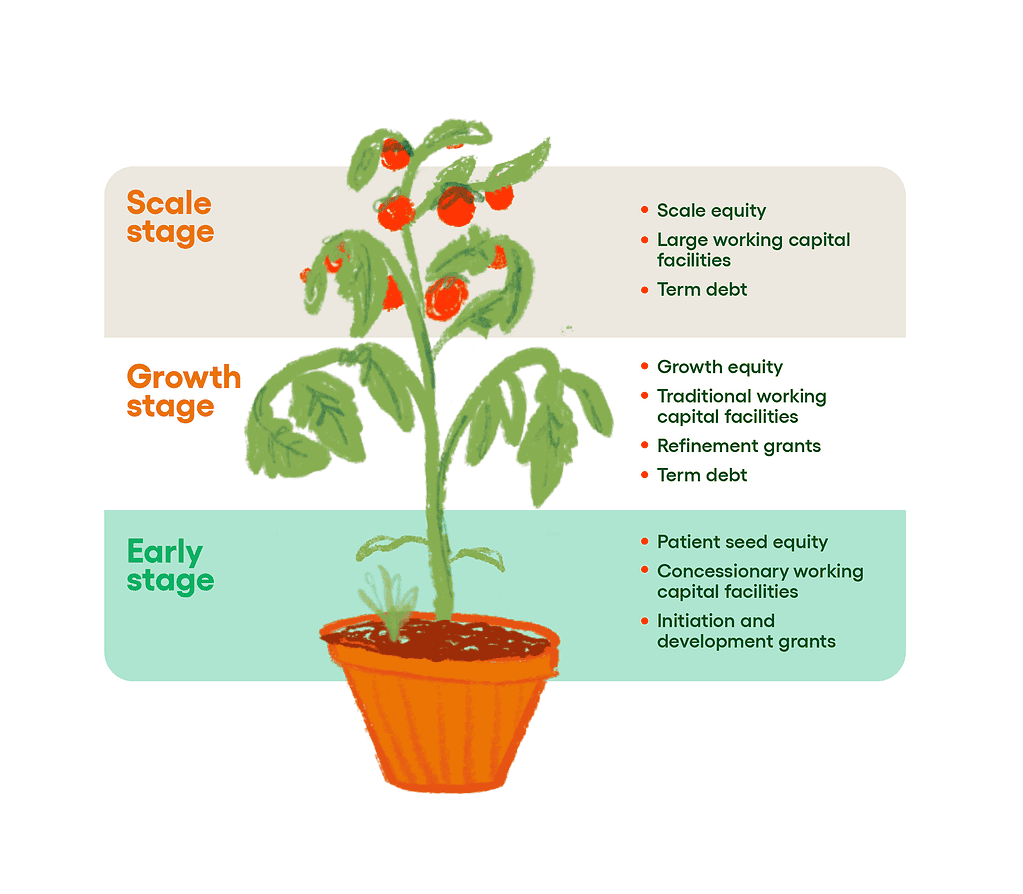

Social enterprises tackling climate adaptation in emerging markets need time, flexibility, and the following types of capital:

- Grants enable companies to research and develop products or services, and to support ongoing business development. Grants also allow companies to operate in emerging markets, where value chains still need to mature and attract more specialized businesses. They act as a de-risking tool, especially in the face of climate change, and remain important after investment and well into the growth stage. For example, Gulu Agricultural Development Company (GADC) used a grant from DANIDA, the Danish development agency, to pay for and embed farmer training into its model.

- Seed equity (Seed or Series A) enables companies to invest in a team and cement their product-market fit. It supports CapEx for companies with high customer acquisition costs operating in low-margin value chains, and it is also often a key for unlocking working capital. Acumen’s agricultural investment initiative, Trellis, offers Patient Capital at this stage, like in the Warc example described below.

- Working capital allows companies to meet their cash needs given their business cycles. Working capital is critical to operations at every stage of company growth, but particularly so for early-stage business using on-time payments to build trust-based sourcing relationships with smallholder farmers. Lenders like Root Capital, MCE Social Capital, and Rippleworks offer working capital loans to agribusinesses, and Aceli Africa helps unlock working capital and debt financing by incentivizing local banks.

- Growth equity (Series A to B) comes in when companies have proven out their unit economics and are ready to build and hire for scale, and unlock access to debt. Investors like DOB Equity and ARAF come in at this stage, offering investments from $1 to $5 million. DOB Equity, for example, invested in Coconut Holdings to support the expansion of the business and unlock more opportunities within the value chain.

- Scale equity (Series C and beyond) enables companies to expand into national or international markets, capture significant market share, and create a competitive advantage. For many agribusinesses, strategic buyers are often noted as the most likely to provide this type of capital.

- Other types of capital include long-term debt for investing productive assets, various tools for hedging foreign exchange exposure, and more unique instruments such as revenue sharing arrangements.

Agri-SMEs need different types of capital throughout different stages.

Investors we spoke with largely agree: when all these instruments are available to an agribusiness at the right time, scale is possible and value is unlocked for the sector. But investors also agree that this is rarely the case, noting three major gaps in the ag sector’s capital continuum.

Working capital

Every agribusiness needs working capital at nearly every point in its journey. It allows companies to pay farmers on time, manage complex operations, and navigate the financial ups and downs of seasonality. But solutions on offer are too expensive, and many firms still fall in that missing middle. Many agribusinesses typically need smaller ticket sizes, and yet most minimum loan sizes start at $200,000. Investors like Aceli Africa, Root Capital, and MCE are working to address this gap. Aceli Africa, for instance, lowered its minimum loan size to $15,000 to enhance accessibility to working capital for early-stage agribusinesses. As companies build their collateral base, they need better access to this type of capital, and early-stage equity is often key to unlocking it.

Early-stage equity

Early-stage companies that have ambitions to scale broadly or to shift a market significantly need a long runway, CapEx, and money to hire and retain talent. Early-stage equity often plays the role of master key for these needs, unlocking a range of other financial instruments, including working capital for a longer runway and term debt for CapEx. As one debt investor we spoke to stated, “When companies already have equity, it makes providing that working capital a lot easier.”

There is a significant lack of early-stage equity for agribusinesses. Estimates from ISF indicate that less than $500 million of equity was invested into agricultural firms in sub-Saharan Africa in 2022, with the majority going to digital-only ag tech companies. While this gap is present in many emerging markets, the longer timelines and higher risks of agriculture exacerbate the situation.

Redefine VC in Africa, and set the correct benchmarks and expectations.

Hetal Patel, 54 Collective VC

Commercial models for early-stage equity usually default to venture capital, where one successful investment can return 10x to 40x and pay for eight other investments that failed. Agriculture — physical, tangible agriculture — does not work that way. Growth rates are slower and margins for most commodity crops are tighter. The venture capital model is a poor fit for companies that work with smallholder farmers, especially those in Africa. As Hetal Patel, formerly with Mercy Corps Ventures and now Chief Investment Officer at 54 Collective VC, said, we need to “redefine VC in Africa, and set the correct benchmarks and expectations.”

What could redefined equity look like? We can be more intelligent in how we parse the market. Digital-only ag tech plays can still attract venture capital. But for early-stage investments in on-ground firms, we need more patient, blended finance to reflect the risk and timelines that we know exist. Melissa Tickle from FINCA Ventures agrees, “[Investors] need to be more realistic about the growth trajectory and return profile of the agribusinesses they invest in, so that they (or another co-investor) can more appropriately allocate different types of capital at different stages of the business.” Setting the correct expectations and baking in what we know about future funding needs will allow investors to build the right kind of vehicles that can grow young companies.

Scale equity

But early-stage equity, even patient equity, only works and motivates more players to join this investment stage if there are some returns down the road. For venture capital, those returns typically come from secondary exits to scale investors, acquisition, or public offerings. The last can be almost entirely ruled out for agri-SMEs operating in emerging markets, and the other two are currently lacking. Corporations looking to improve their geographic reach, build value chains, and improve their operations may be interested in strategic buyouts of SMEs, demonstrating increasing promise as an exit path for companies. Yet impact investors could do more to position SMEs as attractive targets for these investors.

[Investors] need to be more realistic about the growth trajectory and return profile of the agribusinesses they invest in.

Melissa Tickle, FINCA Ventures

This is not a problem unique to smallholder agriculture. A recent report asked agri-food tech investors across the globe, “Why haven’t we had more agri-food tech exits in the past 10 years?” Fifty-five percent of those believed that the industry is still young and exits are coming; 20% thought not all agri-food tech could produce exits in venture timeframes. Those problems are exacerbated in higher-touch, higher-cost models.

Amanda Turner Ege from elea states, “The impact investing ecosystem needs to evolve in the way players think about exits. We all need to think more about how our investment strategies create value for investors and founders in subsequent rounds. We also need to consider innovative exit models like India’s SME IPO market, management buy-outs, impact-linked finance, and partial exits.” If the typical venture capital model is not the right fit for early-stage equity, then we likewise need to find the model that scales and operates companies profitably.

There are agricultural-focused private equity firms in Africa, but not enough of them, and not operating at the scale we need. Companies such as RMG Concept Group also reward early-stage investors so they are able to make more investments. Not all of these outcomes will have Silicon Valley IRRs, and that’s okay: higher average returns would be great, but what the sector actually needs is more predictable returns. Tamer El-Raghy, Managing Director of the Acumen Resilient Agriculture Fund, said, “If we want to catalyze more capital into agriculture in emerging markets, we need proof points. We need scalable business models demonstrating predictable risk-adjusted returns and successful exits. But without predictability and successful exits, a significant amount of capital will remain sidelined.”

We also need to consider innovative exit models like India’s SME IPO market, management buy-outs, impact-linked finance, and partial exits.

Amanda Turner Ege, elea

Mapping the trajectory for Warc

When Warc Africa was founded in 2011, the company initially worked with smallholder rice farmers in Sierra Leone and trained them on regenerative agriculture practices. The founders started out as many entrepreneurs do: investing their own capital and fundraising through family and friends. Very few institutions are able to take on the level of risk required to lend to agribusinesses, but Acumen was one of their first institutional investors when we invested in 2019.

Since our investment, the company has pivoted significantly to find a sustainable market opportunity. They still train farmers on regenerative agriculture practices, but they now operate primarily in Northern Ghana in the maize value chain, providing inputs and market access to farmers through a network of 80 trading hubs.

Additionally, in the last year, Warc received a working capital loan from Rippleworks and an investment from the Swiss family office, Kielder Agro. Kielder Agro’s investment will allow Warc to expand geographically or vertically, going deeper in the value chain.

Without predictability and successful exits, a significant amount of capital will remain sidelined.

Tamer El-Raghy, Acumen Resilient Agriculture Fund

The pivots and iterations that Warc went through were made possible by having access to grants, innovative debt providers, and Patient Capital. It took a few years for the company to experiment, iterate, and find its niche. Now, we are seeing the fruits of that patience. By providing market access to smallholder farmers, Warc is increasing farmers’ incomes and unleashing a massive market opportunity.

Smallholder agriculture needs more solutions like these. When agribusinesses like Warc have access to the right capital, at the right time, and through difficult pivots, they can improve their model and scale their impact. Beyond the impact incentive, Warc demonstrates a clear market and investment opportunity. Our equity capital enables companies to capture value from agriculture by correcting market inefficiencies and, in some cases, creating markets.

Ag-investors need more collaboration and new investment paradigms

If we want to scale innovative agribusiness in emerging markets, the starting point is more capital. Philanthropic capital, in particular, plays a critical role in de-risking early-stage agribusinesses. But that capital has to be fit-for-purpose, applied with a deeper understanding of the emerging agricultural landscapes and systems that the capital is flowing into, and with an honest set of expectations of what is likely to flow out. This means far more collaboration across impact investors and, likely, entirely new investment paradigms.

The stakes are high. Agriculture has the potential to uplift 75% of the world’s poor out of poverty. Smallholders, who produce 35% of the world’s food, will play a decisive role in future climate mitigation efforts and the world’s ability to feed a growing population. But without the right capital instruments across a well-defined capital continuum, and without the right set of investor expectations, innovation risks falling behind the rapidly accelerating climate crisis.

Featured photo courtesy of Kentaste

More from Acumen

$90M commitment for Pakistan Agribusiness Climate Adaptation

Acumen announced at COP29 an initiative to support 13M smallholder farmers, promote gender-inclusive development, and enhance agriculture and food security.