An Agribusiness Model Built on Village-Level Sourcing

Through village-level sourcing models, agribusinesses can unlock opportunities for impact at scale and financial growth.

- Blog

- Sustainable agriculture

- Cross region

“If you build it, they will come.” But if an agribusiness is far from the farm-gate, smallholder farmers (SHF) will only come if the roads haven’t been rained out, they can afford to rent a truck, and there is no other buyer with a better price. Rather than waiting for farmers to come to them, a number of Acumen’s agriculture portfolio companies are building their businesses close to the farmer through village-level sourcing models. Village-level sourcing models are a type of decentralized business model where agribusinesses strategically place agents, often along with small physical outposts, in communities to buy product from farmers. These models are critical for agribusinesses that want to scale their impact, unlock market opportunities, and grow financially.

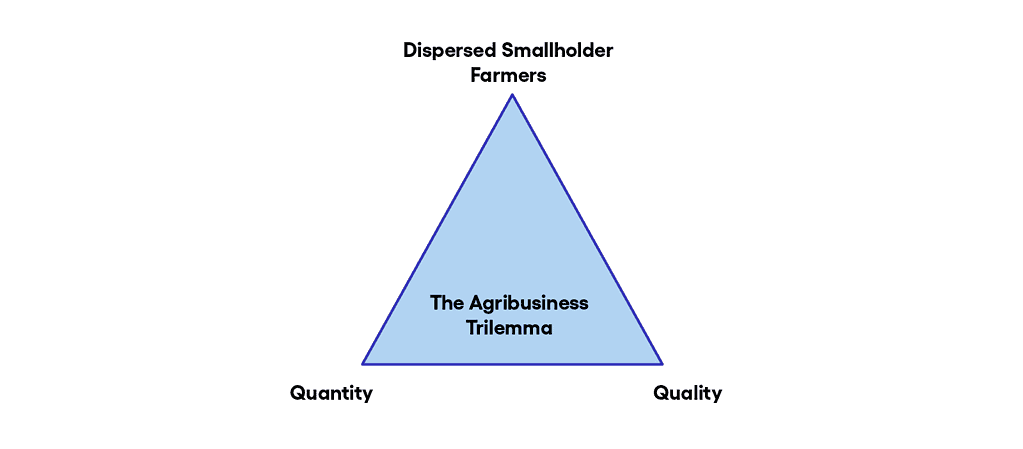

If village-level sourcing models enable agribusinesses to reach more farmers and provide easier market access, why aren’t they used more widely? The easy answer is that they’re difficult to implement. Smallholders are geographically dispersed and have different farming practices, making it difficult for companies to buy sufficient volumes directly from farmers at a standard level of quality. This is no easy feat, but as we will see, the impact and the value creation are worth the undertaking. We will share what it takes, in our experience, to make these models work for agribusinesses.

Village-level sourcing models in agriculture

Several of our companies are deploying village-level sourcing models to move point of purchase closer to the farmgate, provide smallholders with key inputs and services, and improve farmers’ incomes. IDH’s research on commission-based agent networks highlights that these models tend to operate in value chains with high levels of informality, less effective market coordination, and weaker value chain governance. Unlike centralized models, village-level sourcing models do not require farmers to bring their products to larger towns or a central market, thereby decreasing or altogether eliminating transportation and logistics costs for smallholders. Village-level sourcing models offer farmers a consistent, nearby buyer, allowing them to sell more product and increase their incomes while also providing a route to scale for agribusinesses.

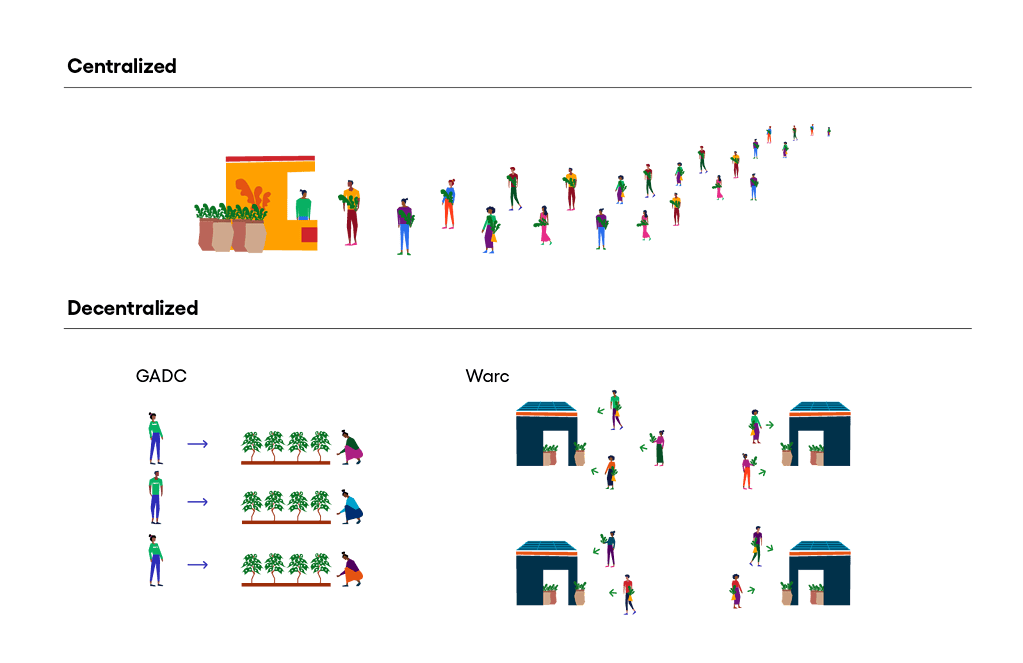

In a centralized model, farmers have to travel to larger towns or a central market to sell their products. In a decentralized model, companies go to the farmers to buy their products.

Consider, for example, Gulu Agricultural Development Company (GADC), a Uganda-based agribusiness that deploys over 190 agents with cash to buy cotton directly from farmer communities. According to GADC founder, Bruce Robertson, a village-level sourcing model is the only way the company can reach dispersed smallholders in Uganda. In order to meet the high demand from international buyers, the company has to buy from thousands of farmers, which is only possible through agents that go directly to farmers.

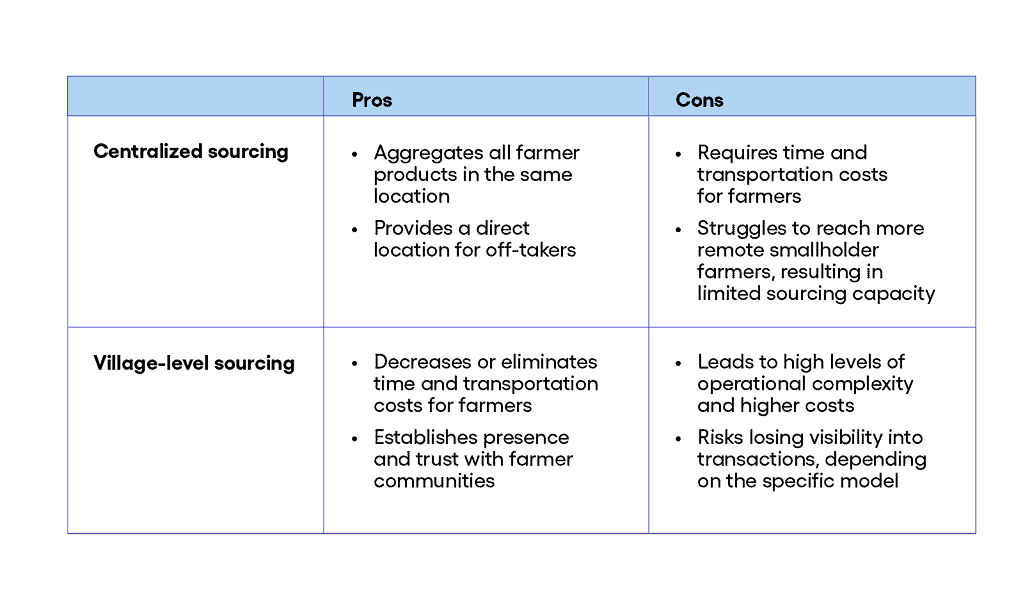

Centralized sourcing models have their own benefits, but village-level sourcing models tend to be better suited to serve smallholder farmers.

Issues in Agribusiness Growth

When we asked our companies why there aren’t more agribusinesses reaching 100,000 farmers through these business models, the consensus was clear: the operational management is where agribusinesses fail to reach scale. And when they try to scale too quickly without nailing down the operations, the businesses themselves can fail forward.

The challenge is that companies need to source from thousands of farmers spread out across broad swaths of land, and farmers have to grow products at the same quality specification and at the right volumes to meet buyers’ needs. The complexities continue: farmers work across different soil types and microclimates with different farming practices, and companies must source consistently while also maintaining viable profit margins.

As we will see through two examples, overcoming this trilemma requires a foundation of trust with smallholders, the ability to compete on price, and a surgical precision in the implementation of the decentralized business model.

Warc Africa: Trust and trade hubs

- Current SHF reached: 20,000

- Target SHF reached: 100,000

Warc Africa is a vertically-integrated agribusiness that operates through a decentralized network of trading hubs. The company buys maize, shea, and soybean at a competitive price, and resells to large domestic traders and food processors. The company’s trading hub model consists of a network of physical outposts managed and run exclusively by women from the communities where the hubs are located. To retain product quality, the hubs offer improved inputs and storage capacity, and agents are trained to check grain moisture levels. Warc has established 80 trading hubs that now serve 20,000 farmers total, and are looking to scale up to 100,000 farmers and source over 100,000 tons of maize.

The nature of the maize value chain lends itself to a village-level sourcing model for three reasons:

- Commodity crops are about volumes, not margins. Warc has to buy thousands of tons of maize from farmers in order to meet buyer minimums and to generate profit.

- Physical trading hubs enable the company to hit those target volumes and buy smaller amounts from thousands of farmers, as opposed to traditional purchasing practices that buy large volumes from a small number of farmers.

- In value chains like maize, traders and buyers are more opportunistic and can take advantage of farmers. Warc’s decentralized model with pricing transparency counters this, creating a consistent company presence in the community.

Warc’s ability to buy smaller volumes from thousands of farmers offers smallholders a consistent buyer, thereby building trust with farmers through fair and transparent prices. Years of underpaying and exploiting smallholders has eroded trust between agribusinesses and smallholders, making fair purchasing practices the foundation of rebuilding the relationship. Warc displays their competitive prices to farmers, and almost all payments are done through mobile money. The company found that mobile money reduced the business complexity of paying in cash, streamlining the payment process. In addition, a majority of farmers were willing to adopt this technology in exchange for the value they received from selling to Warc.

By providing transparent pricing to farmers and employing women from the community at the hubs, Warc is rejecting the transactional, business-as-usual relationship between agribusiness and farmers, and instead, building a relationship based on trust and value-add.

“We become part of the community. We’re not just someone who comes in and out. With an agent, you have to focus on big transactions, but with physical infrastructure, we build trust with the farmer and we can serve everyone.”

Warc CEO Chris Zaw

Coconut Holdings: Agents for the last mile

- Current SHF reached: 4,000

- Target SHF reached: 10,000

Coconut Holdings (CHL) sources coconuts from a network of 4,000 smallholder farmers along Kenya’s coast and processes the coconuts into a range of products, including virgin coconut oil and coconut chips, which are then sold in Kenyan supermarket chains. Coconut Holdings buys from farmers using two channels: Buying clerks, who are full-time employees responsible for purchasing, harvesting, collecting, and delivering the coconuts to collection centers; and Village-based agents (VBA). They are contracted, commission-based purchasers who travel to the farmers to buy from them. While CHL sources most of its coconuts through the collection centers, VBAs enable the company to hit quantity targets in case of drought or other unexpected events.

Unlike buying clerks who are limited to purchasing from registered CHL farmers, VBAs are mobile and can reach unregistered farmers in more isolated areas. Today, CHL works with five village-based agents, providing each VBA with an advance based on their estimation of how many coconuts they will be able to buy. The company trains VBAs to act as micro-entrepreneurs and businesses, wherein they have to plan their logistics and transportation based on the advance given to them. The tradeoff is that while CHL does not have to coordinate the logistics, they lose some visibility into the negotiations and transactions between agents and farmers. Upon the VBA’s delivery of coconuts to CHL, the agent is paid a commission per coconut.

Both employees at the collection centers and VBAs are trained to identify the right quality of coconut, based on its maturity and size. Additionally, through a demo farm, Coconut Holdings can demonstrate that their training interventions and higher quality inputs have led to an improvement in coconut quality. These measures allow CHL to have slightly more control over the end product’s quality.

Opportunities for decentralized business models

Both Warc and Coconut Holdings prove that village-level sourcing models can mean better incomes for smallholder farmers and real growth opportunities for agribusinesses. We’ve only scratched the surface of what decentralized business models could look like through these examples of village-level sourcing. When companies begin to explore decentralized storing and processing in addition to sourcing, they open up massive opportunities for impact at scale and financial growth.

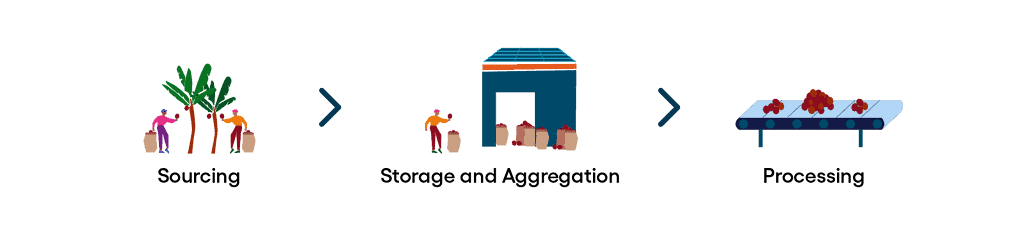

Agricultural products follow a sequence of sourcing, then storage and aggregation, and finally processing. Agribusinesses that source at the village level may begin to explore village-level storage, aggregation, and processing.

Many agribusinesses that source from smallholders recognize the critical need for storage and aggregation capabilities, and processing is the next step in the value chain. Agribusinesses that take on more of these roles along the supply chain have the potential to capture more value for farmers, correct inefficiencies, and in some cases even create new markets. That potential, however, is balanced by the humbling nature of the operational complexity. To create and replicate these models successfully, we’ll need thousands of talented entrepreneurs up to the challenge, and heaps more Patient Capital.

Acumen’s early-stage agricultural investment initiative, Trellis, plans to invest more heavily in different iterations of decentralized business models, track the operational drivers to success, and help to validate the models to catalyze more commercial capital. Agriculture has the potential to uplift 75% of the world’s poor out of the vicious cycle of poverty. The market opportunity and the impact case are there; we just need to invest in them.

More from Acumen

Experts weigh in on the agriculture capital continuum

What does a healthy agriculture capital continuum look like? We spoke to ag-investors about the types of capital that agribusinesses need.