Powering income generation in Africa: productive energy use

- Blog

- Renewable energy

- Cross region

Everything you touch or do today, every bite of food, every piece of clothing, every trip to the store, takes energy. It is essential to economic production; it literally fuels progress. But the opposite is also true. Without abundant, affordable energy, there is no modern agriculture, no efficient transportation, no way of linking villages and cities. That lack of energy is strangling economic growth in large parts of sub-Saharan Africa.

For decades the strategy around energy and African economies replicated the American example: build a big grid and people will find ways to use it. What this didn’t take into account is that the U.S. built its grid in the 1930s when copper, timber, coal, and capital were much cheaper.

Today in Africa, the strategy is very different. The stunning rise of off-grid PAYGo solar showed two things: first, that solar and batteries are now affordable enough to be deployed at scale in rural Africa, and second, that financing assets for rural households and businesses can unlock incredible growth. Innovators and entrepreneurs are heeding those lessons, and using them to break down the barriers between supplying energy and providing a use for it that will power livelihoods.

A new wave of companies are welding off-grid renewable energy to productive, income-generating appliances, driving economic development for people living in poverty. They are bringing solar-powered irrigation to farms, solar freezers to markets, and electric vehicles to the streets of African cities. In 2022, Acumen launched PEII+, an investment initiative into these productive use of energy (PUE) companies. Examples of PUE companies include:

- SokoFresh, a Kenyan company that provides smallholder farmers with access to mobile cold rooms to reduce food wastage and sell produce in regional and international markets.

- Winock, a Nigerian company that sells and finances solar systems and other efficient appliances for microbusinesses.

In a recent 60 Decibels survey, 77% of farmers who used SokoFresh’s cold rooms reported an increase in income, with one farmer saying, “My income has improved tremendously since I started cooling my produce because I have very few losses.”

We believe that companies like SokoFresh and Winock, that are building decentralized, renewable infrastructure, are essential to increasing the productivity and incomes of low-income households throughout Africa. But we still have a lot of questions: How big is the PUE sector now, and how big could it get? How does a PUE company grow, and what is the ideal capital mix along their journey?

7 Charts for Productive Energy Use (PUEs)

To dig into these and other questions, we leveraged the excellent Big Deal database along with historical data from PitchBook. We coded the database using Acumen’s criteria for a PUE company: a company whose main source of revenue is derived from the sale or use of assets that generate net income increases for micro- and small enterprises (MSEs), including farmers. We included all asset types, and did not filter by energy source, as many companies sell a mix of renewable and fossil fuel-powered appliances.

We excluded i) all companies for which PUE was not their main source of revenue (e.g. residential-focused solar home system companies that sell larger systems and appliances); and ii) companies which did not directly reach MSEs or farmers (so very few commercial and industrial (C&I) solar providers or platform-based companies).

Here are seven charts that show you what we found:

1. The PUE sub-sector is growing rapidly

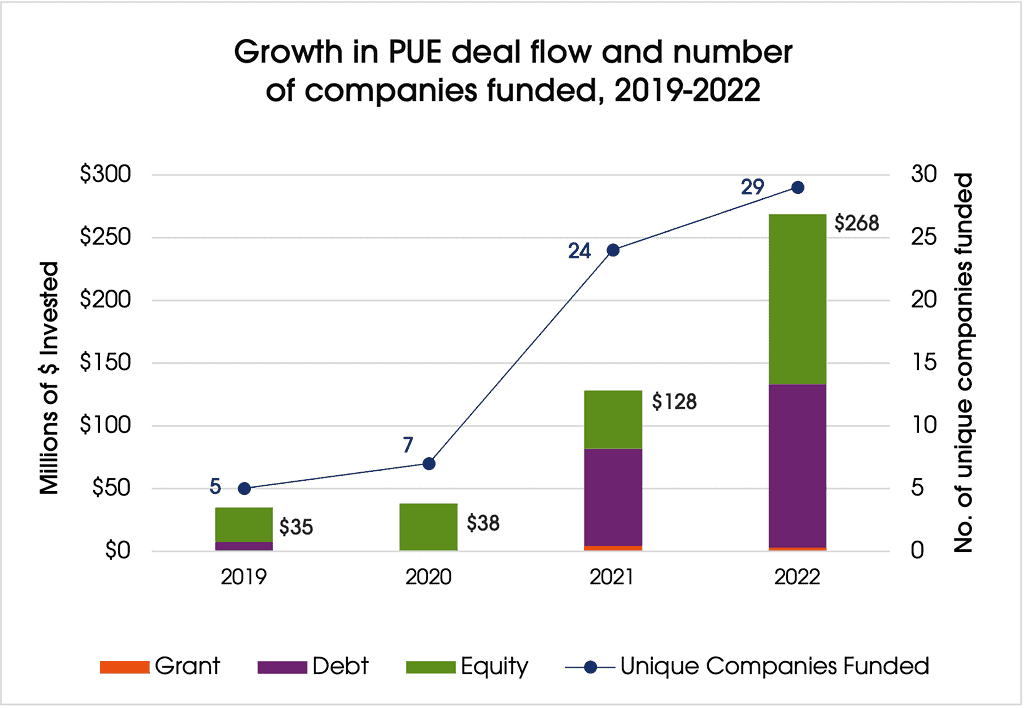

In 2019 $35 million was invested in PUE companies (including grants, debt, and equity). By 2022 that number rose to $268 million.This means the sub-sector doubled on average every year with a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 97%. In 2022, when the African venture scene barely grew, PUE deals were up 109%.

The volume of capital has been driven by just a few companies (see below), but the number of companies being funded has grown. In 2019, just five companies were raising funding. That number grew to 29 in 2022. Even if we limit ourselves to just measuring commercial capital (debt and equity), the number has still grown from five in 2019 to 21 last year.

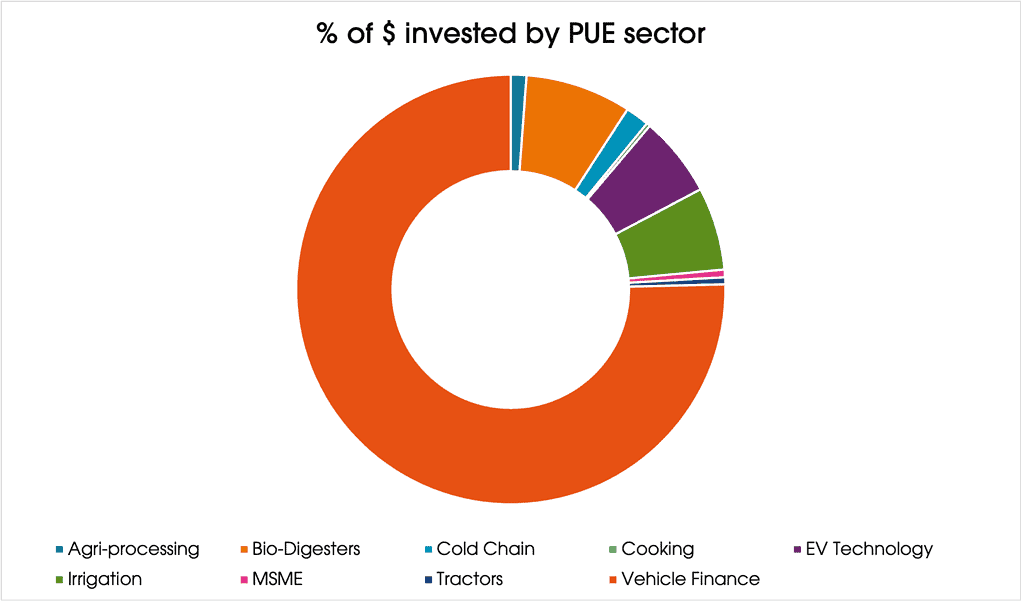

2. Vehicle Finance drives the most investment

The PUE sub-sector is driven by transportation: specifically car and motorcycle finance for taxi drivers (primarily internal combustion engines, but increasingly electric-powered as well). This is fueled by the growth in African cities and the ubiquity of ride-hailing services. These services play a crucial role in PUE: they have created an unprecedented demand for income-generating vehicles AND an ideal channel for asset finance. Lenders are able to verify identity, assess income and reputation, secure repayment flows, and track asset performance. This data and analysis, if applied to other income-generating asset classes — admittedly a big if — could unlock equivalent growth.

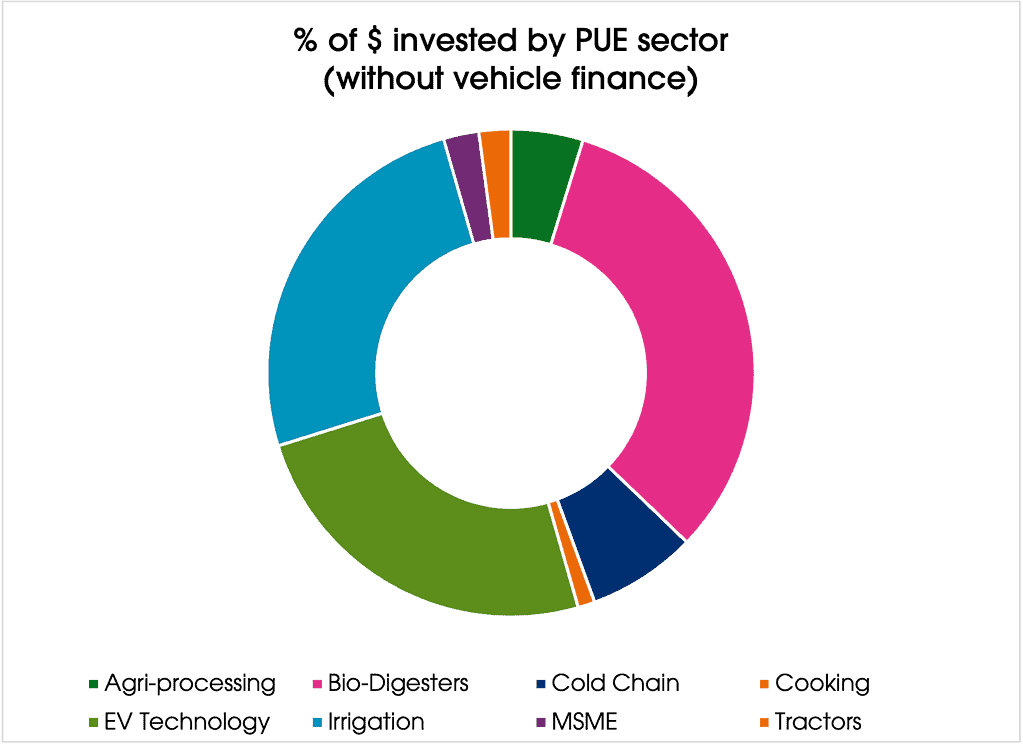

3. Electric vehicles, irrigation, and bio-digesters also garner a lot of interest

If we filter out vehicle finance, we see three other categories co-leading the way: electric vehicle technology, irrigation, and bio-digesters. Electric vehicles certainly have some overlap with vehicle finance, but what is encouraging here is the long tail: at least 11 different companies have reported funding, and five of those have raised over $1 million.

The other two categories (irrigation and bio-digesters) are each driven by one large company (SunCulture and Sistema.bio, respectively, both of which have received investment from Acumen-sponsored funds). Conversely, investments in cold chain solutions are driven by a number of investments at smaller ticket sizes: eight companies have raised funding, with a select few raising over $1 million.

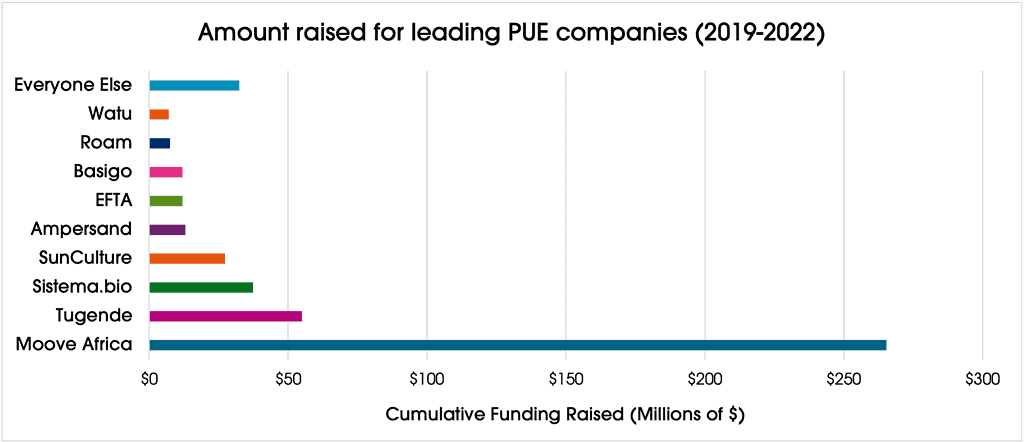

4. Most funding flows to a handful of companies

The top four PUE companies have raised 82% of all funding and the top nine have raised 93%. Moove Africa has raised 57% by itself. We believe this is more about the nascent nature of the space, and we expect many more companies to raise significant capital in the next five years.

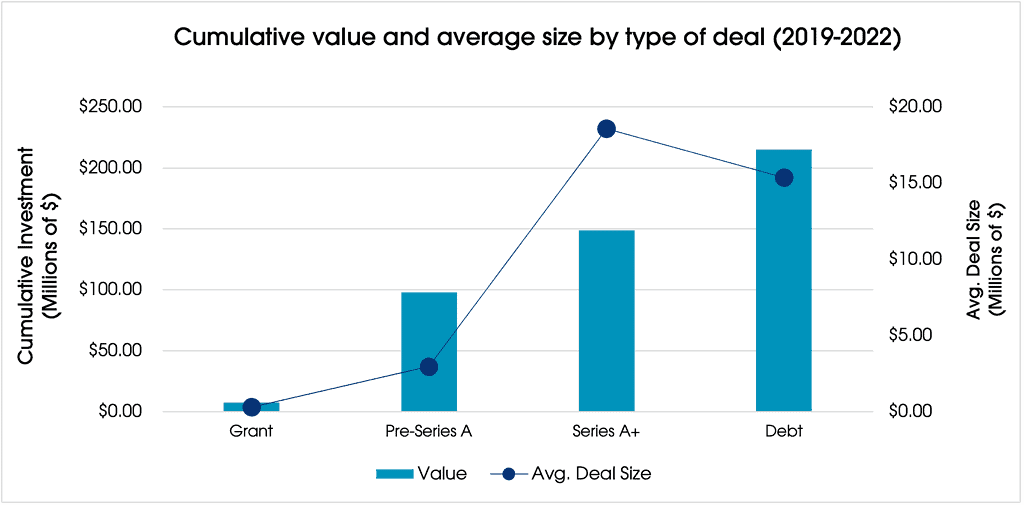

5. Debt financing makes up half of all funding

Half of all PUE funding, in dollar terms, has been debt finance, with early-stage equity making up most of the rest. But crucially, only five companies have raised debt finance, and all of them have raised $9 million or more, with an average deal size of $15 million.

Yet 33 companies in total have raised non-grant capital, which means there is an exciting crop of companies coming up that are working to perfect their models. This speaks to the nature of PUE: it takes time and equity capital to validate, but once that work is done it remains capital-intensive and requires heavy amounts of debt to scale. The availability and cost of that debt is what will determine the size and profitability of these companies.

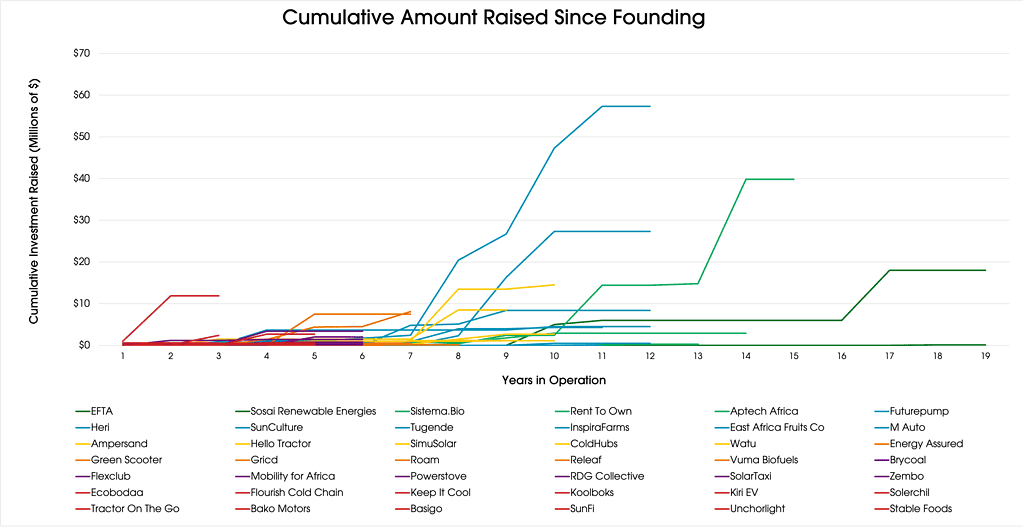

6. It takes 7-16 years to build a company that can raise $10 million

This chart shows how much cumulative funding different companies have raised since the year of their founding (note: Moove Africa is excluded, lest it break the Y-axis). It has historically taken 7-16 years to build a company that can raise $20 million. But there is some indication that timelines are shortening: we see a cluster of young companies (orange and red lines) raising capital earlier than their predecessors; Moove and Basigo surpassed $10 million within their first two years

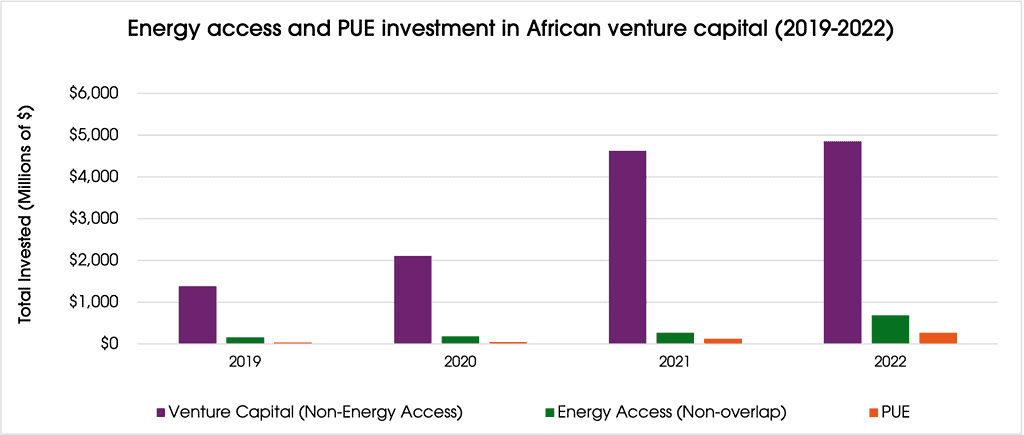

7. PUE is still a nascent sub-sector

PUE receives a fraction of African venture capital, but it has grown from 2.5% to 5.5% in the last four years. Going forward, we hope that PUE will be a growth area. Our expectation is that tech-enabled financing of productive assets will grow quickly, while more vertically-integrated models that combine assets with other services, such as working capital or value chain linkages, will see more moderate growth but with deeper impact. These vertically-integrated companies are crucial for ensuring that PUE has beneficial impacts on people in poverty.

And that is the point we’d like to close on: impact. PUE appliances are, at the end of the day, about empowering businesses and improving livelihoods. Winock saves entrepreneurs money that they would have spent running generators; SokoFresh helps farmers get paid more for their crop and allows wholesalers to buy fresher produce in greater quantities. These are the types of business models that increase incomes and put food on peoples’ tables. To make a dent in the massive problems they are confronting, they need more capital. Let’s keep growing.

More from Acumen

5 lessons for investing in East and West Africa

From tackling post-harvest loss to unlocking resilience in smallholder farmers, Acumen’s 2024 investments offer bold strategies to overcome East and West Africa’s toughest challenges and drive lasting change.