Transforming Agriculture in Africa: Bain & Company’s New Report

- Blog

- Sustainable agriculture

- Cross region

With 80 percent of the world’s poor working mainly in farming, fighting poverty is inextricably intertwined with changing the status quo of agriculture. As climate change presents farmers with challenges from severe drought to locust infestations, the urgency of these efforts is only increasing.

Acumen began investing in agriculture in 2008, and has since invested over $35 million in 29 early-stage enterprises serving smallholder farmers across 14 countries. We began investing with a focus on increasing farmers’ yields, with the thesis that helping farmers produce more and higher-quality crops would enable them to increase their incomes. Over the last 12 years, we have come to see that we and many other enterprises were focusing solely on the farmers’ productivity—how they grow their crops and how they can maximize their productivity—at the expense of a more holistic approach to address both farmers’ productivity and their connection to markets.

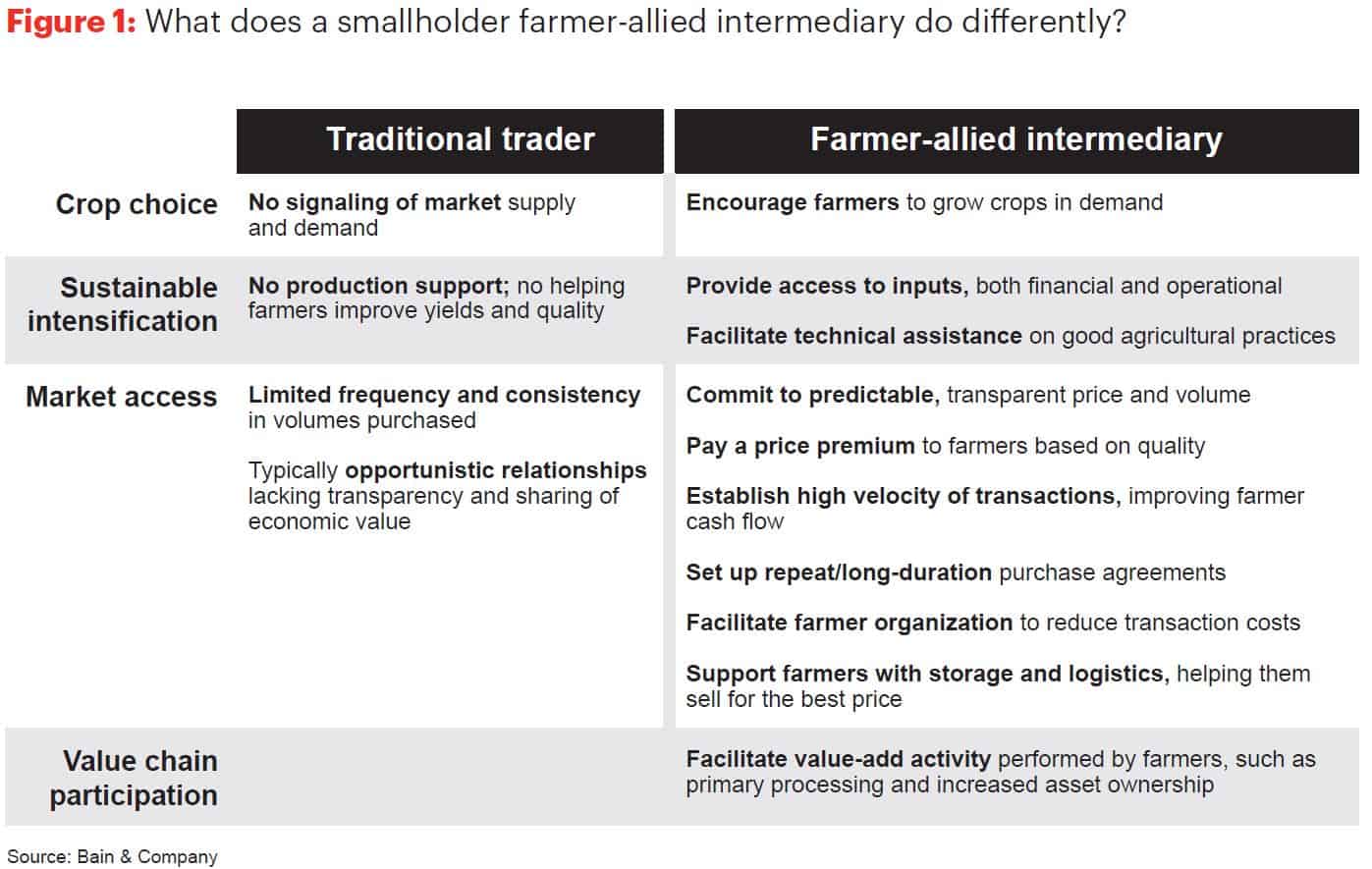

Acumen collaborated with Bain & Company in the development of their report, published today, to chart a way forward for the sector. Based on research and insights from Acumen as well as Root Capital, Technoserve and others, How Farmer-Allied Intermediaries Can Transform Africa’s Food Systems, suggests an approach built around “farmer-allied intermediaries,” or agriculture businesses that “strategically and intentionally source from smallholder farmers” in a way that improves the status quo.

These farmer-allied intermediaries not only provide inputs and train farmers on how to maximize their yields but also advise on in-demand crops, seasonal crop rotations and introduce basic processing capacity, all of which multiply potential income for farmers; finally, they then connect them directly to buyers.

In Kenya, Acumen East Africa investee Kentaste purchases coconuts from nearly 2,000 smallholder farmers at consistently high volumes and fixed prices—ensuring that, no matter how the global market’s coconut prices fluctuate, its farmers will always make the same steady income for what they produce. To help ensure consistently high yields, Kentaste sells farmers low-cost inputs such as seedlings to plant more trees and provides training from pest management to soil regeneration to bookkeeping. To save farmers significant labor expenses and maximize their profits, Kentaste staff harvest the coconuts and transport them to its factories for processing into premium coconut milk, oil, cream and flakes. With this model, Kentaste has increased coconut farmers’ earnings as much as 120 percent.

Across our agriculture portfolio, we are seeing farmed-allied intermediaries pave the way with these holistic models in high-value cash crops like coconuts, cocoa and coffee. But cash crops alone will neither provide these livelihoods at scale nor create a more stable domestic food system. Sub-Saharan Africa particularly needs these staple-crop-focused farmer-allied intermediaries for cereals such as maize, millet and rice. As Bain & Company’s report highlights, despite their available farmland and being one of the world’s largest consumers of cereals, sub-Saharan African countries too often have to import them: between 1970 and 2010, cereal imports to the region increased 5 percent each year.

To make the kinds of changes needed for farmers and consumers at scale, we need more farmer-aligned intermediaries dealing not just in high-value crops but also in lower-value staple crops. Because the margins are lower, these businesses will need to be even more creative and have more coordinated support around them to make smallholder farmers profitable.

Acumen investee WARC Group is working towards this in Ghana and Sierra Leone where it partners with smallholder farmers to produce maize and rice. WARC’s “Service Delivery Unit,” or SDU, brings inputs like fertilizers and seeds as well as modern machinery to smallholder farmers’ plots. This commercial machinery is typically used to maximize yields on farms with thousands of hectares and, without WARC, would be inaccessible for smallholder farmers. WARC advises its partner farmers on which crops to grow based on local market demand, and based on seasonal rotations. Between its machinery, training and inputs, WARC significantly reduces farmers’ taxing manual labor and increases their yields. In exchange for WARC’s services, SDU farmers pay WARC with a proportional amount of crops and sell their surplus in local markets for additional income.

WARC’s second business line hires local subsistence farmers for its 1,500-hectare Training Farm, where they learn environmentally-conscious farming methodologies and equipment operation. WARC then aggregates and sells the crops from its Training Farm and SDU farmers locally, gradually helping Ghana and Sierra Leone replace expensive imports with locally grown rice and maize.

Because early-stage staple companies like WARC inevitably have lower margins, they are riskier investments for capital providers: they have lower target return profiles, longer time horizons to reach scale and less clear opportunities for exit. For Acumen, the company’s high potential to change Africa’s food systems—for the benefit of smallholder farmers as well as national populations—is worth the risk. This is what patient capital was designed to do—to back companies focused on solving problems of poverty sustainably and for the long run.

Sub-Saharan Africa needs more of these agribusinesses, especially working in staple crops. But, as report authors Vikki Tam and Christopher Mitchell write: “There are far too few of them, and those that do exist are not able to grow fast enough. Agriculture is a system, and for farmer-allied intermediaries to grow profitably, a wide array of actors will need to come together to support them and help amplify their impact….Intermediaries can’t get there entirely on their own.” While farmer-allied intermediaries are the most promising models for changing Africa’s agricultural system, they need other actors up and down the chain—from governments to investors to foundations to banks to food corporations—to enable their success.

We need all the actors in the sector to collaborate in order to accompany these enterprises. This will require more:

- Investors to support these companies with patient capital that allows for lower returns for sake of sustainable impact and scale over the long-term. This is especially needed given that food and agriculture account for only 9 percent of total assets under management for impact investors.

- Foundations and philanthropists to shift their focus from models that change individual farms’ outputs to collaborating to transform entire value chains.

- Governments to make it easier for farmer-allied intermediaries to succeed, from offering tax incentives to input subsidies to paving the way with better infrastructure—especially for low-margin models dealing in staple crops.

- Large food companies to seek out and buy from these early-stage intermediaries—at high volumes that will guarantee a large, stable demand and with quality-based price premiums—to help them grow. As the Report says, this serves companies’ business interests, too, by: “helping them to better manage supplier risk, increase employment in the countries where they operate, and optimize tax incentives for local sourcing.”

Looking ahead, Acumen intends to explore investing in more farmer-allied intermediaries like WARC while accompanying our existing investees—from guiding them through tough decisions to introducing them to new partners—in their journeys to changing their communities, their nations and continent.