The risk and reward of bringing modern energy to hard-to-reach markets

- Blog

- Energy

- Sub-Saharan Africa H2R

In a world where electricity is an everyday convenience for billions, there are still 675 million people living without access to this essential resource. A staggering 80% of these individuals reside in sub-Saharan Africa, their lives out of the spotlight, and lacking the opportunities that electricity could bring.

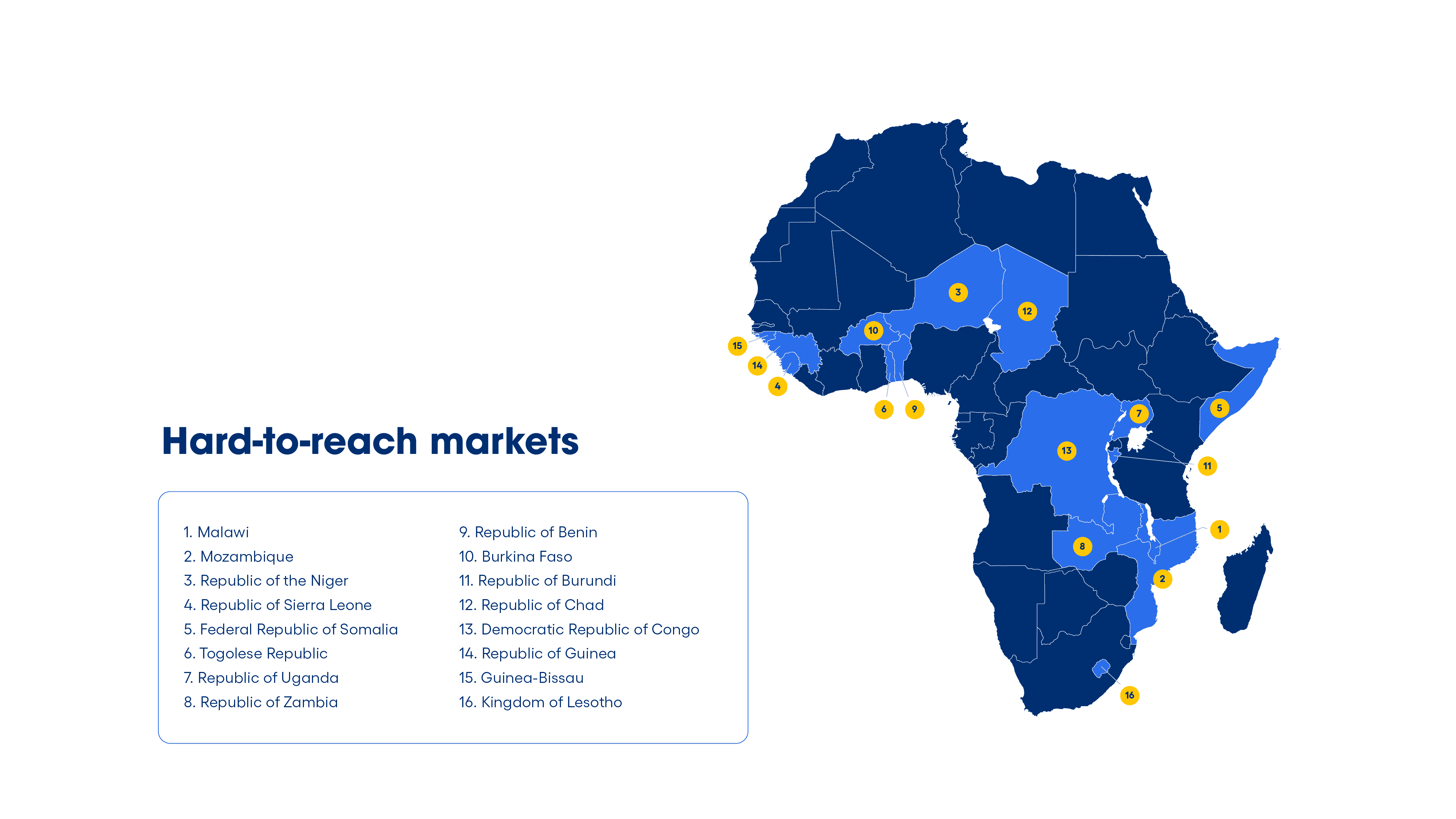

Amidst this challenging landscape, a group of 16 sub-Saharan African (SSA) nations remain largely overlooked, their streets and households unelectrified. These countries, some of the region’s least developed economies, with electrification rates at or below the sub-Saharan African average and high rates of poverty, are desperately awaiting the surge of investment that could illuminate futures and forge pathways out of poverty.

We take a quick look at some of the key features of hard-to-reach markets, exploring the risk and reward: why investors hesitate, but also how the tide of opportunity could be turning. For people living in poverty and vulnerable in the face of climate change, the time is ripe for bold interventions that could brighten the prospects of millions and have transformational impact.

The Risk

Challenging operating environments, underdeveloped infrastructure and weak currencies are endemic to least-developed economies (the end result of a vicious cycle of colonialism, underinvestment, dependency, and extraction). Investors are wary of three main factors:

Challenging Operating Environments: It is hard to import goods, get operating licenses, or enforce contracts. In the World Bank’s last Ease of Doing Business Index (before its discontinuation for flaws in its conception and execution), hardest-to-reach markets ranked (on average) 145th out of 191 countries.

Underdeveloped Infrastructure: These markets are literally harder to reach. Almost half the population live outside walking distance of an all-weather road. Mobile subscriptions are 10% lower than the African average.

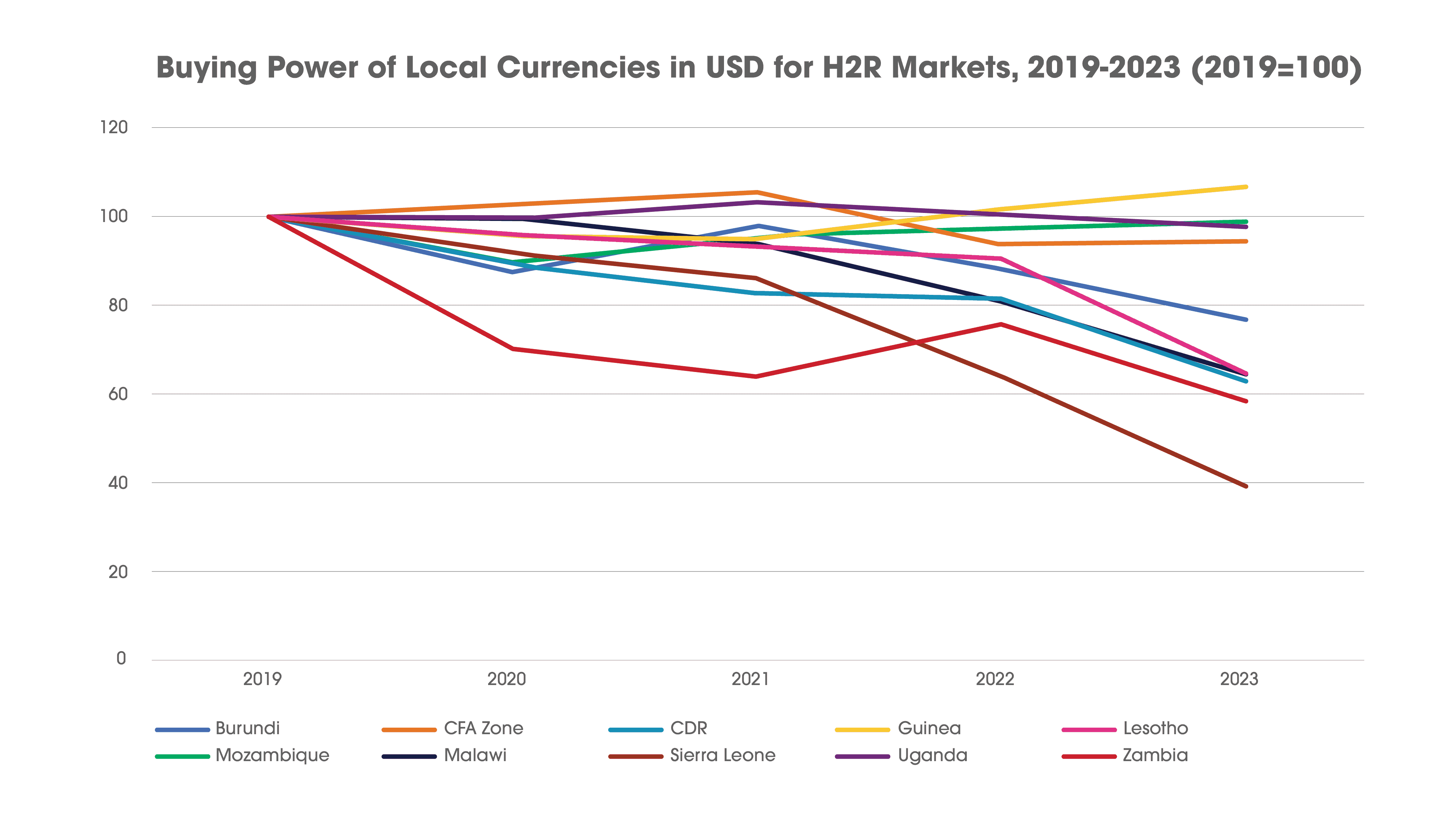

Weak Currencies: There are 11 currencies in these 16 markets (five countries use the West African CFA). Since 2019, the average currency has lost a quarter of its buying power, making foreign investment harder to attract and more expensive to repay.

Embedded in all of these factors is the question of politics, and therefore of policies. Stable politics and strong policies attract investment, but many hardest-to-reach markets lack one, or both, of these. For example, the security situation in the Sahel is fraught; Four countries in the region have seen an introduction of military rule since the start of 2021. There is also a lack of a consistent, enabling policy environment that can deter investment. In Zambia, for example, companies received tax bills in 2020 for imports that had previously been declared duty-free.

Without a stable, consistent administration, it is difficult to address thorny operational and macroeconomic issues. The end result is a high perception of risk, which in turn leads investors to demand higher returns. Investors in these 16 markets expect a 84% higher risk-adjusted return than in an average country worldwide, and even 28% higher than other SSA countries. This high perceived risk self-perpetuates through low investment: countries are punished for having been punished before. Risk-bearing capital is needed to break the cycle, providing success cases for commercial investors to follow.

A multi-country investment approach can mitigate risks by diversifying investments and insuring risk across a broad portfolio, while also encouraging the exchange of effective, context-specific policy between nations.

The Reward

For those willing to embrace these risks, the rewards are significant: creating climate resilience and setting underserved markets on a clean development path.

Climate Resilience

71% of the population of these 16 markets live below the lower-middle-income poverty line, compared to 63% in the rest of sub-Saharan Africa, and these communities are residing in acutely climate vulnerable contexts – in areas facing worsening heat stress, more frequent droughts, more intense floods, and extreme weather events including tropical cyclones. Mozambique’s Cyclone Idai in 2019, for example, not only disrupted lives but also critically hampered energy distribution systems, emphasizing the intricate connection between climate resilience and energy security.

By providing energy that is both clean and climate resilient, households in Africa’s least developed economies will be better equipped to adapt to a changing climate, ensuring a more secure future with enhanced resilience for their livelihoods, health, and wellbeing.

Clean Fuel for a Bright Future

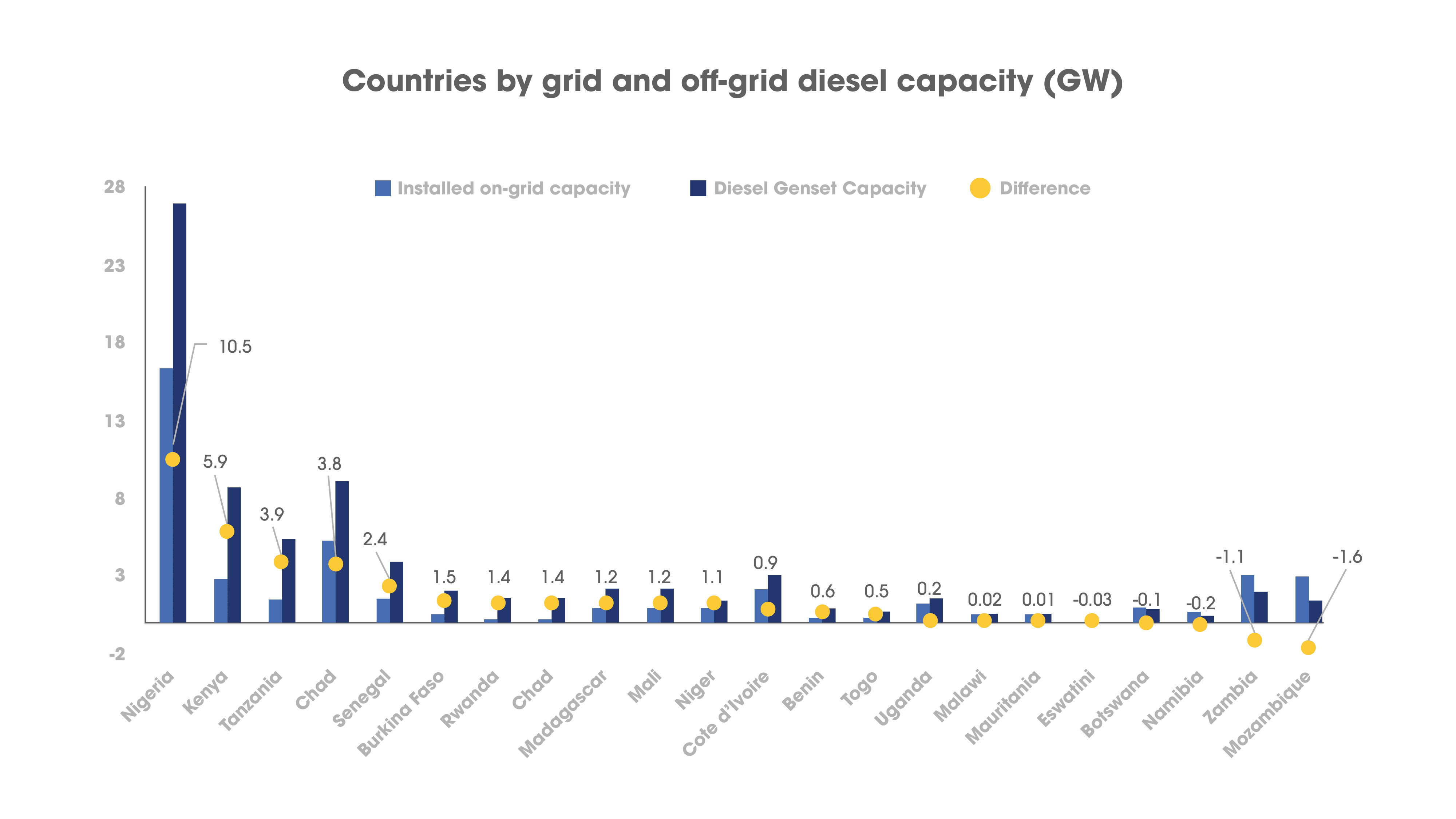

Across sub-Saharan Africa, the demand for energy is increasing rapidly, far outpacing the growth in energy demand seen in other parts of the world. Unelectrified households and businesses are starving for more energy. For example, the electricity consumption per capita across these hard-to-reach markets in 2019 was 155 kilowatt hours, or about enough to power two LED light bulbs for 6 hours a day, about 75 times lower than the annual consumption of an American. At least 17 African countries have more distributed diesel generator capacity than they do grid-connected power-generation capacity, seven of which are among the 16 hard-to-reach geographies. In addition, they are experiencing some of the most severe climate shocks. In Southern Africa, heatwaves have driven annual and seasonal temperatures up by 1.04°C and 1.44°C respectively since 1961 and increased energy demand for cooling across Africa could cost half a trillion dollars by 2076.

All told, African energy demand in 2040 could be around 30 percent higher than it is today, compared with a 10 percent increase in global energy demand. So it matters deeply how that growth is powered.

Sub-Saharan Africa’s contributions to historical and current CO2 emissions have been minimal: less than 3% historically, and at present average 0.8 tonnes of CO2e per person per year, compared to a global average of 4.8 tonnes. Yet these countries are facing demographic and climate pressures: hard-to-reach populations are growing three times as fast as the world average.

In the drive to meet growing energy demands, the continent’s unelectrified countries may default to the readily available but high-emitting fossil-fuel model. In one scenario, an African transition out of energy poverty that heavily relies on fossil fuels, could result in increased CO2 emissions that would offset a 20 percent cut in the emissions of China, the United States, India, Russia, Japan, and Germany combined. But through an inclusive energy transition, unelectrified markets can not only meet their energy needs sustainably, but also play a pivotal role in achieving global climate goals, which must be driven by the efforts of established industrial nations.

Conclusion

The challenges faced by the continent’s most underserved off-grid regions are a significant opportunity. Africa, with 60% of the world’s top solar resources, represents just 1% of global installed photovoltaic capacity. The IEA projects that in rural areas – home to over 80% of those without electricity – mini-grids and standalone systems, primarily solar-driven, emerge as the most promising solutions. Forward-thinking investors ready to embark on this journey stand to unlock desperately needed private investment, and build financially sustainable and competitive markets that will ultimately form the backbone of the continent’s low-carbon future.

This future is not only possible, it’s the only path forward for people and the planet.