The Need for Foreign Exchange Solutions in Africa

Foreign exchange swings are an ever-present threat to many companies' survival in Africa. It's time to explore solutions to foreign exchange risk.

- Blog

- Cross region

Building a profitable, scaled business is like constructing a skyscraper; it can take years before an idea begins to rise above the ground. Even in ideal conditions and enabling markets, it is hard work. In sub-Saharan Africa, the conditions are rarely ideal: even the best businesses are built on shaky macroeconomic foundations. At any moment the shilling might slide, those sands might shift, and down the tower crumbles, regardless of the quality of construction.

Many of the businesses that Acumen invests in, especially in sectors like energy, borrow capital from the U.S. or Europe but sell their products or services to local customers. This creates a structural imbalance: their revenues are mostly denominated in shillings or naira or kwacha, but their funding is overwhelmingly in dollars. When local currencies depreciate (which they do, often), revenues are suddenly less valuable. The implications are severe: companies are unable to order enough inventory, repay their debt, or attract additional capital. In acute cases, they may be forced to lay off employees. In short, foreign exchange (FX) swings are an ever-present threat to many companies’ survival in Africa.

Over the last two years, we have seen multiple successful companies brought to their knees by abrupt drops in the value of the shilling, the naira, and other currencies. Hedging that risk brings predictability but at a prohibitive, unaffordable expense. In this article, we want to make the case for urgently re-exploring solutions to FX risk and offer a place for interested readers (investors, companies, funders) to share their thoughts and ideas.

Why Local Currency Debt Is Out of Reach

In 1999, Barry Eichengreen and Ricardo Hausmann identified a condition they termed the “original sin” in financial markets: any situation in which a country is unable to borrow long-term in its domestic currency. They wrote 25 years ago that in the presence of this mismatch, “financial fragility is unavoidable.” They were writing about sovereign debt. But that same original sin – earning in shillings, borrowing in dollars – persists today for African enterprises, and it is the quicksand underneath the impact they have created.

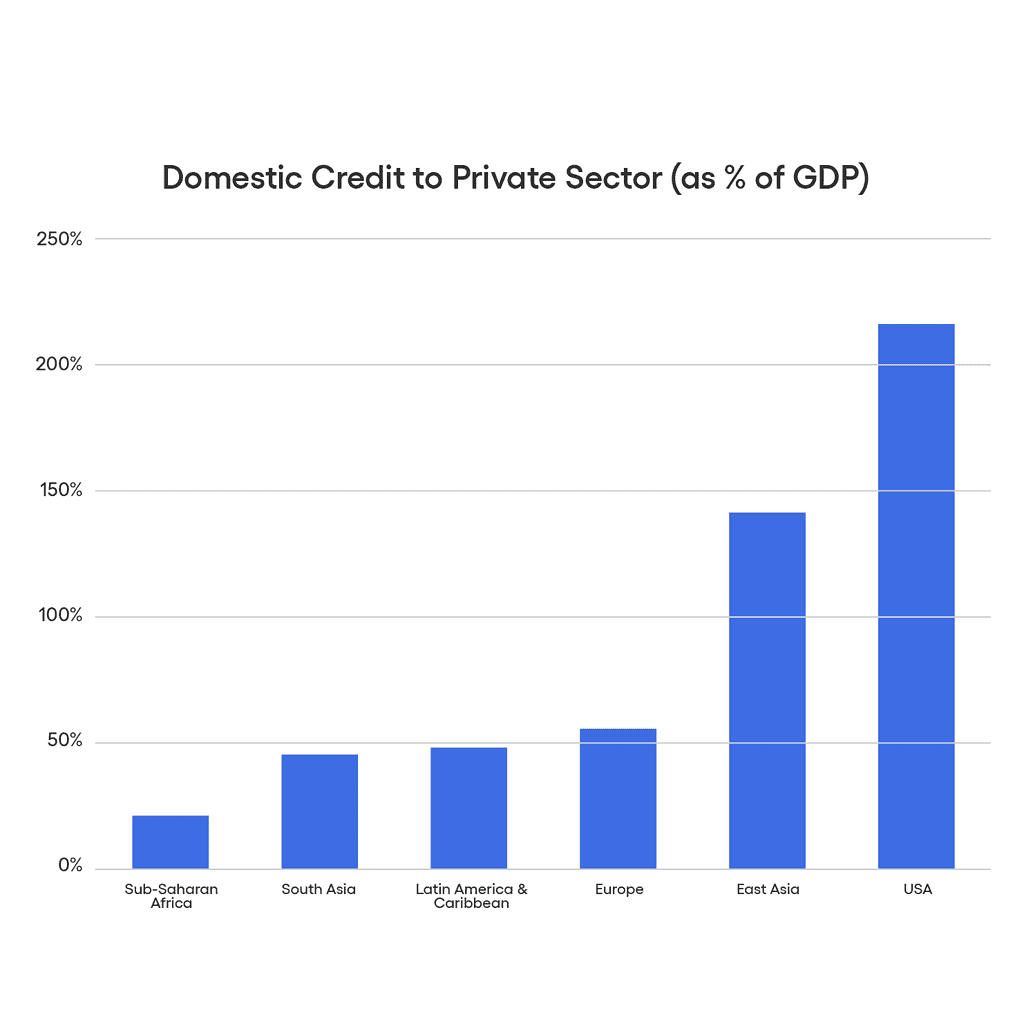

Acumen invests in low-to-middle-income countries, where local currency debt is incredibly scarce. The chart above shows local debt as a percentage of GDP, and the bars are the median market in each of these regions. In sub-Saharan Africa, domestic credit penetration is low. Tanzania, the median market, has only 15.2% penetration. Kenya stands at 32%, while Nigeria is at 14%, and Ghana is even lower at just 12%.

Banks in those markets are well-run, quite profitable, and do not lend to small and growing companies, at least not without 100% or more collateral. Catalyzing more local lending is crucial, but it’s not the subject of this article. Suffice to say, companies in our portfolio cannot borrow in their local markets and are forced to look elsewhere.

International lenders exist, and some of the companies we invest in are eventually able to borrow from them. But much of that debt is denominated in so-called “hard” currencies – Tameo’s most recent report showed that 65% of impact debt in 2022 was in dollars or euros. One way or another, that creates a mismatch.

What does currency mismatch mean for companies?

From January 2023 to January 2024, the Nigerian naira lost more than half of its buying power. The Kenyan shilling lost 22%, and since the new year has appreciated 18%. The swings can be wild, and the dips are severe. Sadly this has been the reality in most of Africa, and throughout the world. Research from TCX shows that in any given year, one in eight low-income countries will see their currency depreciate 20% or more. One in 20 will see a 50% depreciation.

When a currency depreciates significantly, the operational excellence and positive impact of the companies we invest in do not diminish. Their products, talent, and market knowledge do not deteriorate (in fact the opposite). In 2022, the Sierra Leonean leone depreciated 60%, and the Ghanaian cedi lost 50% of its value. For companies operating there, revenues were suddenly worth one-quarter to one-half less to their hard currency lenders, unless they or their investors hedged their loans. And even if they did, short-term currency movements can make a well-leveraged company look exceedingly over-indebted in the short term, which in turn makes raising more capital difficult.

This puts entrepreneurs in a slowly-tightening vice. They can play roulette, and hope that this is not the year their number comes up (this strategy is not uncommon; one-third of impact debt flows were unhedged in 2022, per Tameo). Or they can pay to hedge their borrowing, adding hundreds of basis points (or thousands, in smaller markets) to their already sky-high cost of capital. Instead of making it easier to start a business in the poorest countries on Earth, companies are saddled with an extra tax.

What makes a company viable?

There is a view that hedging costs are merely a manifestation of the overall risk in emerging markets. If the prevailing cost of funds is 16%-20% (based on Aswath Damodaran’s data for the Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC) in emerging markets), but you need to add 8% in hedging costs to make revenues predictable, then you need a business model that works with a cost of capital of 24%-28%.

Unfortunately, there are far fewer business models that work at 26% compared to 7% (the WACC in America). And not so long ago, there were plenty of VC-backed startups that couldn’t make money even when rates were at or near zero.

The unfortunate truth is that the high cost of capital that companies face does not just reflect risk, it creates it. Our portfolio companies run out of inventory frequently, because they lack access to working capital, or are holding excess reserves to cover sudden swings in the value of operating currencies.

If we want to reduce the risk of investing in Africa over the long term, the only way to do that is by facing it today. In markets where users have less to spend, where infrastructure and talent issues abound, doubling the cost of capital is an unreasonable burden for companies. But it’s one that could be lessened.

Our purpose in writing this is to reinvigorate the discussion about more effective approaches to FX risk management, at both a micro and macro level. We’ll be clear right at the start of that discussion: we don’t have the answer. But let’s start with first principles: what should effective financing options for SMEs in emerging markets look like? In our view, they should be:

- Affordable. Debt financing ought to enable growth and profitability, not detract from either.

- Local. Local-currency financing resolves the mismatch between the revenue currency and debt currency. It is strongly preferred, and scarcely available.

- If not local, then equitable. If lending in hard currency, then the cost of hedging macro risks, such as FX movements, ought to be shared between borrower and lender.

- Wholesale. Certain firms, once they’ve become large enough and have low enough funding costs, have no trouble finding local currency funding. We need better solutions for all firms.

- Sustainable. Lenders need to make money as well, and so need to price in their own cost of funds and expected credit losses. Concessional and blended capital may be crucial to fulfilling these goals.

Mitigating FX risk in an affordable way is essential to achieving these outcomes. A number of solutions have been proposed, but not yet implemented. TCX (itself an institution launched to make funding more available for emerging market firms) proposed several initiatives in a recent white paper. Those included a vastly scaled hedging facility, a trust fund for currency risk guarantees, and a reduced dependence on hard cash collateral. An older (but sadly still relevant) OECD paper from 2017 called for more credit enhancement facilities, as well as more DFI-led lending operations that shared currency risk with borrowers.

Some innovative approaches have been tried and succeeded over the years.

- In 2005, Grameen Foundation partnered with a number of donors to create the Growth Guarantees program, which leveraged private contributions to deliver $32 million in guarantees from Citibank to local banks, which in turn unlocked $145 million in local currency financing from 19 MFIs in 12 countries.

- The Africa Local Currency Bond Fund was created in 2012 to help African companies issue local-currency bonds. By 2021 it had invested $229 million in bond issuances of 47 companies.

- And from our own portfolio, in 2020 d.light and African Frontier Capital structured an innovative off-balance sheet financing vehicle to provide d.light with local currency financing. The facility eventually purchased the shilling equivalent of $110 million in receivables, underwritten by the U.S. Development Finance Corporation and Norfund. It was fully repaid in 2024.

The common thread with these approaches is that they are mostly available for more well established companies. Younger, smaller companies remain price takers, with prohibitively high costs of capital. We believe that for companies of a certain smaller size, particularly those creating important social outcomes, first, hedging costs should be shared pari passu between impact investors and investees; second, we need a broader suite of suitable hedging products such as deliverable hedges to address convertibility risk in many of these markets; and third, Development banks ought to explore more structural solutions to reduce the cost of hedging.

How to do this is a matter of some debate. But it’s a debate we would like to hold, and soon. To that end, we are asking anyone interested to fill out this form, which merely expresses your interest in the topic, your willingness to attend a workshop on it in Nairobi, and gives you some space to share your thoughts. Send us your ideas, your case studies, your napkin scribbles. We need them.

More from Acumen

Meet the entrepreneur who’s electrifying Africa

Maya Stewart, co-founder of off-grid solar provider Yellow, is a rising star in Africa’s energy sector. She sat down with Acumen for a conversation about her journey as an entrepreneur, her company’s innovative business model, and her vision for a fully electrified Africa.